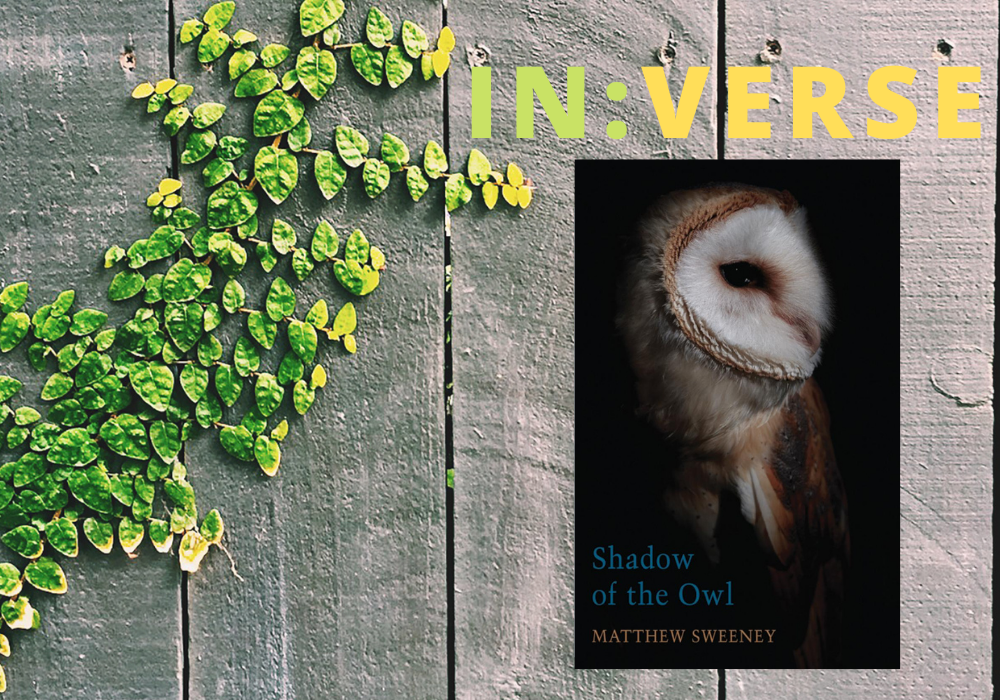

Shadow of the Owl

by Matthew Sweeney | Bloodaxe Books | 103pp |pb £10.99 | 9781780375427

review by Fred Johnston

This reviewer met the late Matthew Sweeney only once, if memory serves. It was one of those after-readings, noisy, gather-round-the-table meetings, and there was neither room nor time for a decent conversation. A pity, as I had wanted to speak with him. Sweeney died in 2018 of the dreadful motor neurone disease, having just published his collection, My Life as a Painter. This present collection was composed during the final year of his ‘battle’ (though that’s never the right word, is it?) with the illness and the miracle is that in such straits one can compose anything at all. But some poets are awkward like that. It stands to reason, then, that the poems offered here are not necessarily pick-me-ups, though Sweeney’s humour, quite dry, pokes through. This collection was a Poetry Book Society Wild Card Choice, and one can only guess that Sweeney would have had a chuckle at the ‘wild card’ bit.

Matthew Sweeney was born in Lifford, Co. Donegal, in 1952. He headed to London in 1973, and by 1976 was a regular face at poet Robert Greacen’s get-togethers in Notting Hill Gate. Present at many of such soirées were those such as novelist Dermot Healy and Corkonian Augustus Young. Chris Rice recalls how afterwards, he and Sweeney retired to the Sun in Splendour pub, where they recited, eux deux ensemble, all the verses of Bob Dylan’s ‘Desolation Row’. Sweeney was to travel widely, living in Berlin and Roumania, arguably accruing to his work a more European than Irish tinge. In the years that followed, his output—including prose—was prodigious, though there was a suggestion that he was not as well appreciated, or known, in Ireland as he might have been. He lived his last years in Cork, where he found many friends, the majority of them poets. In an obituary, The Guardian remarked, nonetheless, that he was ‘one of the most adventurous, life-enhancing and distinctive poets of his gifted generation. Early on, he had developed an unusual poetic approach, less concerned with traditional form than poetic fable.’

That he knew what made poetry tick is quite beyond dispute; but he was not altogether a rhyme-and-rhythm bard. What he seems to have specialised in was the sidelong swipe at life, which, he recognised, neither rhymes nor has much discernible rhythm when it comes down to it. Life lacks order. And so, as demonstrated amply in this collection, life receives an almost conversational slagging, which ironically may be argued to be a particularly Irish approach. If, indeed, his work was ‘life-enhancing’, it was Sweeney’s refusal to apply any poetic gravitas—though the laughter was often dark—that made his often redemptive poems a form of self-salvation. Buile Shuibhne, indeed, complete with the travelling exile.

Sweeney’s partner, lecturer and poet Mary Noonan, has written a concise foreword to this collection. In an interview in The Irish Examiner in 2019, she spoke of Sweeney’s approach to his work—he had mentored her as a novice poet. ‘But I learned from Matthew that a poet doesn’t work in isolation. You could say that no poem is ever written by one person.’ Nothing in Sweeney’s work speaks of any sense of cutting off from the world. He’s always moving. From tree to tree, one might say. He is aware of the need for rootedness and of the dangers of a world internalised. The impending horrors of his disease cannot have been alleviated by, as she tells us, the fact that he was informed of his fatal diagnosis ‘via mobile phone’. Sweeney took the call in a bookmaker’s and ‘he stumbled out into the street, narrowly missing being crushed by a passing car’. The twelve-stanza title poem ‘The Owl’ contains a ferocious rebuke at the manner in which he was treated:

… You cowardly bastard, I roared, and

Sprayed the arrows all over the blackened world.

He has heard an owl calling—the owl, which is a symbol of both wisdom and death. Noonan explains that ‘his habit of writing directly from his unconscious came to his aid as he sat, night after night, converting his distress into episodes in the history of the taciturn owl’. Nonetheless, ‘his final poems are imbued with a lyrical beauty, arising from his great sadness at leaving the world’. One of Sweeney’s poems gives a complete in-your-face description of some of the absurdities and humiliations of illness, stripping away all the customary and anticipated niceties of his craft:

Shit smells like corned beef

when it’s kept in – those old

tins from far-off Argentina

that floated their way to Donegal

when I was a child, long before

the constipation that bedevils me …

(The Bathroom Devils)

But in ‘No-Man’s-Land’ there is a sense of resignation, of finally going over the top into the unknown, and it’s a genre of performance in itself:

The dead are putting on a play tonight

(or is it a film?) in no-man’s-land. We’d

better attend – though what awaits us?’

‘No-Man’s-Land’ was the title given to ‘the realm of spirit and soul’ by psychology graduate Hendrika Vande Kemp in her essay in the Journal of Psychology and Theology in 1983. So Sweeney’s metaphor has form. Whether he knew of Kemp’s esoteric study is another thing. What a poet knows or doesn’t know is a kind of sacred mystery. This is not—and doesn’t have to be—a sad or reflective distillation of last poems. Sweeney was jousting round and about the most final and viciously triumphant of spectres, that of his own demise. The title of the collection is printed on the cover in an almost ghostly blue against black, the words virtually disappearing as a result. Was it planned? The cover photo of a studious owl is by Dutch photographer Arno Van Zon, a renowned snapper of birds and small insects. The bird looks disdainfully to one side. I really do regret not having had a good chat with Matthew Sweeney when I had the chance. To some extent, this brave and affirming collection makes up for it.

***

Fred Johnston

@Kenssington