Olivia Hope explores the artfulness of picture books

by Olivia Hope

MOMA, the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan is renowned for work by the world’s greatest artists. However, you might not be aware that one of its most successful accessibility programmes is Meet Me at MOMA – a special initiative for people living with dementia to access and interact with the art in the New York museum. The starting point for viewing any piece is one simple question: What do you see? A perfect conversation starter to all personal observations of any piece of art – based solely on individual perception, it places value on what meaning we bring when we look at art. During COVID the National Gallery of Ireland implemented a similar programme and along with other facilitators from local arts venues I was fortunate enough to explore art curation through this different lens.

The starting point for viewing any piece is one simple question: What do you see?

As a children’s writer, what struck me about Meet Me at MOMA were the parallels between viewing art in a gallery and the experiences a young child has viewing illustrations in a picture book for the first time. The words in picturebooks tell a story but the children create their own extended story from the illustrations.

Picturebook illustrations are often a child’s first exposure to art and their responses are instinctive. They point at characters, name what they see, and comment on how a scene may remind them of an encounter they have had. The shared intimate moments between an adult and child when reading a picturebook are an interplay of relationships, a two-way flow of information between them – the adult conveying the story in their voices, the child listening and questioning, and the pauses to reflect on what’s next? before they turn a page.

But when they start questioning the illustrations, that is the moment their learning, critical thinking and understanding blooms. The commenting and questioning of art is expected of art critics but in a child these skills expand their cognitive, social and emotional development.

Picturebook illustrations are often a child’s first exposure to art and their responses are instinctive

Rupert Knight from The University of Nottingham notes, ‘If you have watched a young child at home or a child in the Early Years’ setting looking at a picture book, you will perhaps have noticed how intently the pictures are studied. A quality of ‘looking’ that we, as adults, often neglect as we move from the great divide between picture books and ‘chapter’ books. It’s rather like crossing the Rubicon – there appears to be no point of return.’

I wonder if this means that adult readers underappreciate or underestimate the worth of picture books as a result? Advocates of picturebooks are usually children’s writers, illustrators and the publishers themselves – we have a vested interest, obviously. But there is evidential proof of the impact of picturebooks that early years specialists in education, psychology and social science attest to.

When a child looks at a picturebook a whole myriad of processes occur which is why they are such a crucial tool in a child’s development. Younger children don’t set out to learn – they are curious by nature but don’t fully intend to master skills the way older children and adults do. With picture books they learn incidentally through visual assimilation. Incidental learning is more effective and more efficient, but most importantly is more enjoyable. And picture books are fun! How much a child can learn from an illustration that would take a thousand words to explain, from maps and diagrams to representation of families, communities, role models and sparking new interests. Picture books have it all.

Recently in the British Education Research Journal, Rowan Oberman (of Dublin City University) showed exactly how picturebooks play seven key roles in a child’s educational development:

That one little story, less than eight hundred words with fourteen key images can have such a huge an impact on a child’s growth and view of the world. Is there any other art form that can literally transform a child’s development as much for the better?

To read anything one needs the ability to see and interpret specifically shaped lines and make the association to a linked sound. Visual literacy – creating meaning from images, is an important precursor to reading. A child can read a book on their own through the art, even though they might not have the ability to read letters. They can build their own unique version of a story by interpreting the pictures. If you ask them, they will tell that incredibly special story in their words. This is the oldest form of storytelling – the oral tradition. A child with no formal reading skills can still explain what is happening in a story by speaking about the illustrations: something our earliest ancestors did through cave art.

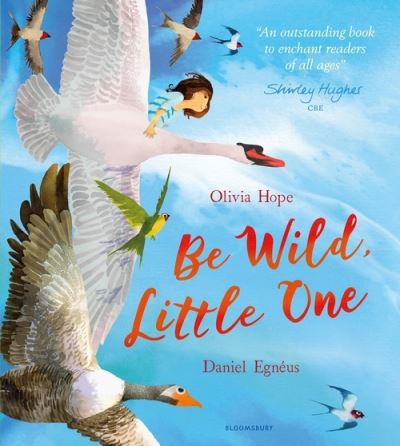

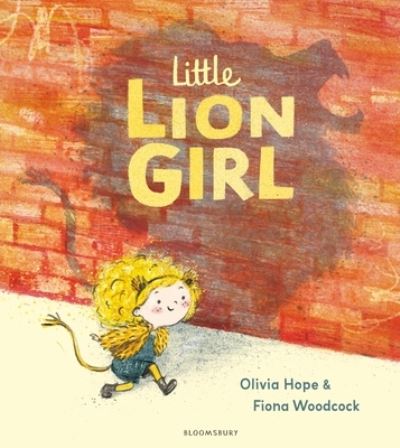

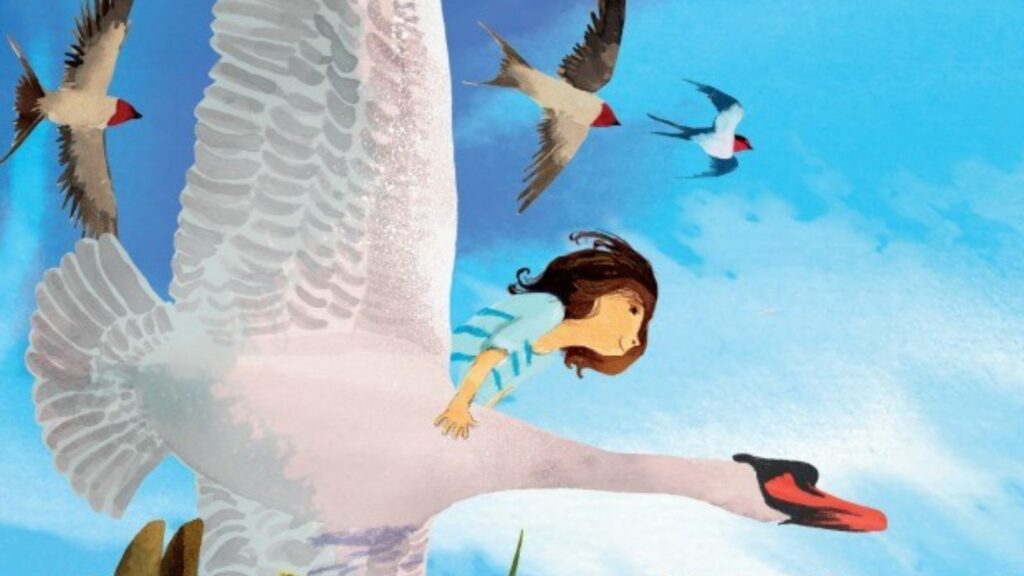

I’ve been fortunate enough to share my picture books with children in libraries, classrooms and book shops. There are times when illustrations from Be Wild, Little One or Little Lion Girl are blown up on a giant whiteboard screens, and I ask the same question for each two-page spread of illustration to spark discussion.

What do you see?

I know my stories well but I am forever impressed by what children tell me they spot in the art by illustrators of my stories Daniel Egnéus and Fiona Woodcock. The hidden chameleon, the child that looks like they’re flying, a puppy in a handbag, the woman dressed in peacock attire. The artistic decisions made by Daniel, Fiona and their designers are deliberate. It is not enough that they consider the story literally and base their illustrations accordingly. Ultimately, how a child sees the story matters more than my words, because although we all hear the same lines, we glean different meanings from what we perceive in the art. Everyone notices different things which means there is a universe of possibilities in picturebook art.

how a child sees the story matters more than my words, because although we all hear the same lines, we glean different meanings from what we perceive

As timeless as cave art, as sophisticated as art criticism and boundless in potential – here’s to picturebooks. You’re never too old to read a good picturebook so next time when you look at the art, ask yourself: What do you see?

Olivia Hope is a children’s author from Killarney, County Kerry specialising in younger illustrated fiction. Her debut Be Wild, Little One illustrated by Daniel Egnéus was nominated for a Children’s Books Ireland Award, the Carnegie Awards and UK Literacy Association awards.

Her latest book illustrated by Fiona Woodcock is Little Lion Girl. Olivia and Fiona will be speakers at this year’s Children’s Books Ireland Conference, September 20-21