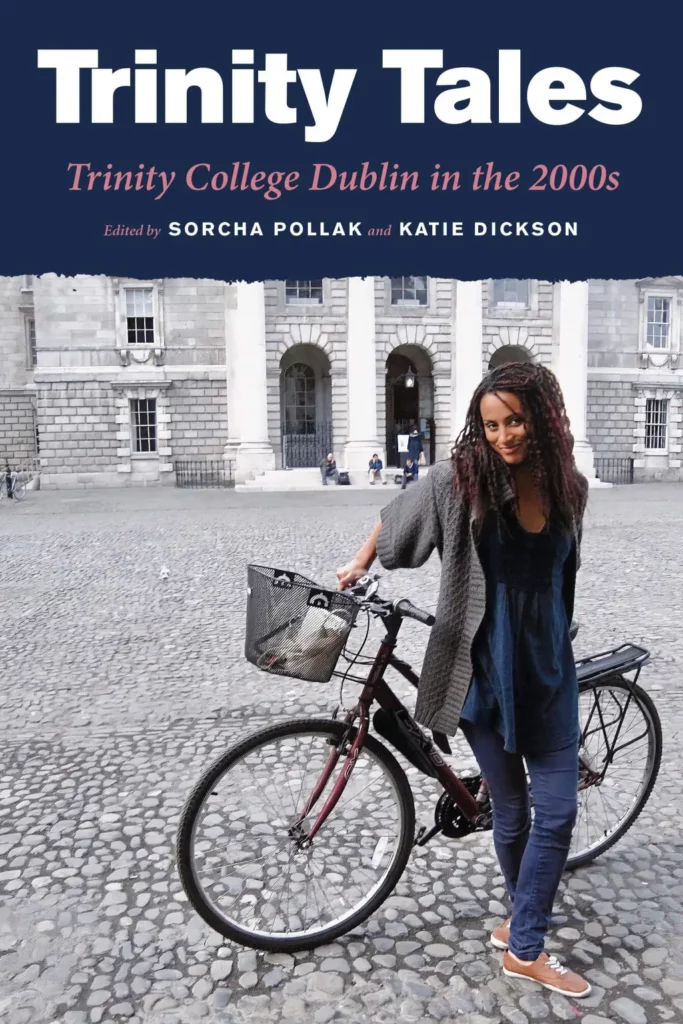

Trinity Tales: Trinity College Dublin in the 2000s|Eds; Sorcha Pollack & Katie Dickson| Lilliput Press|€20

“For those who did not study at Trinity, it may both alter the view that Trinity is exclusive and also embed it further”

—Eoghan Smith on a worthy collection which captures an array of voices and perspectives on student life.

Trinity Tales—Capturing a Decade

by Eoghan Smith

Does Trinity College hold such a special place in the Irish imagination – so much so that it warrants no less than five anthologised recollections of former graduates – or is it that Trinity confers on itself such a claim, as if it is scripted by an ancient, commanding hand in Latin on the graduation parchments?

And let us assume for a moment that it does occupy a privileged space, why does it, and what is the nature of that privilege?

Reputation

No other college in Ireland has the tourist value of Trinity – most people who visit the campus are not even students or staff – and no other college has a reputation for elitism that is so forbidding to the wider Irish public (at least one contributor to this collection admits they didn’t even know you could just walk through the front arch from College Green).

It has, undeniably, an unbreakable sense of its own identity and a capacity for self-mythologising.

The Trinity Novel

Consumers of Irish literature in recent years have also become used to hearing the phrase ‘the Trinity novel’, referring to works by authors such as Belinda McKeon, Sally Rooney and Louise Nealon.

A fourth writer, Catriona Lally, a graduate of Trinity who features in this collection even recounts being asked if she considered herself ‘a Trinity writer’ by professor of English and poet Gerald Dawe. Wisely, Lally said she was not.

Trinity Tales: Trinity College Dublin in the 2000s is an enjoyable compendium of experiences by graduates of Trinity in that exciting, hedonist decade.

For former students of the college, it will no doubt deepen the sense that Trinity is a special, even magical, place that opened up enormous opportunity; while some of the contributors recount negative experiences, nobody says they wished they had never set foot on the old cobblestones.

For those who did not study at Trinity, it may both alter the view that Trinity is exclusive and also embed it further.

Varied styles

This is because there is no attempt to disguise – thankfully – that Trinity draws high-achieving and wealthy students, and that it continues to set exceptional standards in education for which it is rightly celebrated here.

At the same time, judicious editorial selection by the editors Sorcha Pollack and Katie Dickson has ensured that people who benefitted from the increasing diversity of Trinity’s student body are included, demonstrating that Trinity’s work in access is real, meaningful and important.

Including a foreword by Senator Ivana Bacik and an introduction by the editors, Trinity College Dublin in the 2000s contains thirty separate pieces.

The styles of writing vary widely: some are essays that adopt a critical or sociological eye on Trinity and its place in Irish society at the time; others are short personal recollections that focus on a narrow range of events, experiences or interests the author developed during their time in college.

A number of the tales adopt the form of miniature bildungsromane or Künstlerromane – coming-of-age, journey of self-discovery type stories.

These are perhaps the most interesting, as they speak directly to the central mission of education, which is to provide for a truly transformational experience.

Genuine accounts

But whatever the approach, throughout the accounts are genuine: Dickson states in the introduction that ‘she believed that by revealing the authentic tales of those who graced its cobbles from 2000 to 2010 we would open people’s eyes to what the real ‘noughties’ Trinity was like’. In this regard, the collection succeeds.

As anyone who has been to third level or who works in the sector knows – and this is not particular to Trinity College – adjusting to life in college can be extremely challenging for a whole variety of reasons.

Stripping out the ‘Trinity-ness’ of the collection, the book captures these challenges very well – contributors write openly about mental health problems, academic struggles, personal issues in their own lives that affect their college life, financial difficulties, and the whole host of typical issues that befall students in colleges across Ireland.

Class barrier

One other persistent, unignorable challenge emerges: the class barrier.

There are some contributors who, by virtue of their backgrounds, experienced a jarring disconnect between themselves and their (stereotypically) south Dublin, privately educated counterparts or other students from Britain and further afield who came from unimaginable backgrounds of wealth and privilege.

This sense of disconnect, one suspects, enhances the image, even among some of its own graduates, that Trinity is not ‘for them’.

Indeed, some of the most interesting contributions come from those who maintained this perspective on the College and how they had to learn how to come to terms with it.

It is welcome, then, that the editors have included the accounts of students who came through the Trinity Access Programme or who are from backgrounds that do not have the kind of privileges typically associated with Trinity students.

Themes

A number of key themes emerge across the collection – the challenges of ‘fitting in’; the opportunities for growth and development the college afforded; the coming of the digital revolution; the cultural and economic dynamics of Celtic Tiger Dublin; the nascent sense of change that would within ten years give way to immense social and cultural transformations in Ireland; and the increasing diversity of the Trinity student profile through migration and better access to education.

Although there is some unevenness in the quality of the contributions, taken in the round, the collection admirably captures an array of voices and perspectives across a representative spectrum of Trinity students in the 2000s, and overall it is an engaging portrait of ten years in the intellectual, technological and cultural life of Dublin in that transformative decade.

From the perspective of the present, many of the people included are those who would go on to shape Irish life and culture in significant ways. For this alone, the collection is a worthy piece of social and cultural history.

A personal Trinity Tale

I entered Trinity College in 1995 to study History. On the first day I befriended the Scottish daughter of the Duke of Hamilton who was distantly related to Queen Elizabeth, and the son of English nobles who had land and investments that stretched all the way to the far east (this lovely boy would subsequently be killed in a bomb attack in Bali just a few years later).

Within the first week I had met the great unrequited love of my life, who provoked in me a kind of intense, prolonged torment that would make Rilke ashamed he had written ‘You who never arrived’.

I did not help myself in projecting to those around me a disarmingly cavalier attitude to study, but which was in reality an immature lack of discipline towards actual work and a chronic absence of self-confidence.

My ruinously teenaged heart smithereened, my grades plummeting, and my scarf flapping about in the cold March wind, I would secretly drop out before the end of second year in mixture of embarrassment, bewilderment and self-recrimination.

I had been, I knew, badly acting a part for which I had not properly rehearsed. Some time later I returned to university, but this time to UCD. Less obviously storied than Trinity, Belfield’s gigantic suburban blandness was the antidote to the ludicrous, fraudulent self-image I had cultivated at Trinity.

And yet, for many years after I was heard to say: I got my degree in UCD, but I went to college in Trinity.

Eoghan Smith is the author of The Failing Heart (Dedalus 2018). His second novel, A Provincial Death is out now with Dedalus.