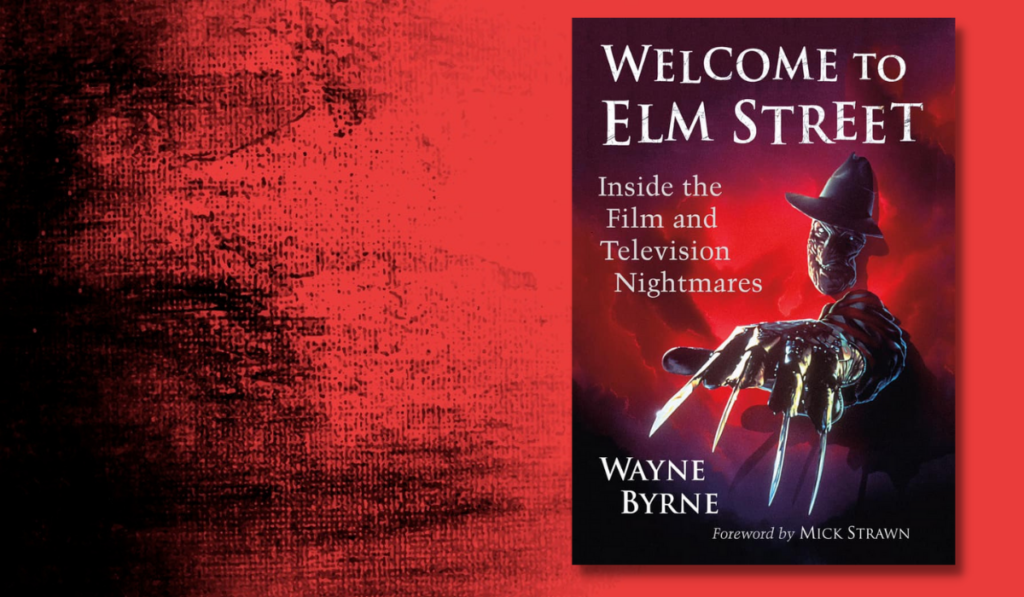

Wayne Byrne talks about growing up with horror movies and how the subtext of the Freddy Krueger films led him to write his book, Welcome to Elm Street.

A New Line kid

I was five-years old when I fell in love with movies, but I wasn’t a Disney kid, I was a New Line kid.

My childhood wasn’t spent in the company of Mickey Mouse and his innocuous cartoon colleagues, but with Freddy Krueger and the damaged denizens of Elm Street.

The New Line logo was a recurring image of my youth, an emblem inextricably linked with the Freddy franchise. New Line is known as ‘The House That Freddy Built’ thanks to the dream demon’s exploits affording the humble, low-budget New York distribution and production company the industrial might to become a formidable major Hollywood studio.

The golden age of VHS

I grew up in the 1980s golden age of VHS and the video shop.

Here in Naas we had Screen Test on the Dublin Road and Hollywood Nights on Poplar Square, and they were my film school. Unlike all the colleges that turned me away, I was always welcome to study Film within those wondrous video libraries.

There were no teachers or textbooks, just these black boxes displaying ostentatious cover art.

There I could marvel at Charles Bronson’s grimacing granite face advertising Death Wish II; I could gaze at Dolph Lundgren’s greased muscles and blonde mullet adorning Masters of the Universe; and most apropos, it is where I was beguiled by the twisted visage of Freddy Krueger as he mugged menacingly on the poster for A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors.

Horror movies

I was blessed with parents who didn’t mind that I enjoyed these movies which some people may consider inappropriate for young viewers; I think horror movies are best enjoyed and most effective when we consume them as innocents, before we get older, wiser, more cynical, and aware of the true horrors of the world.

Honestly, if we waited until the age of eighteen, as the censor’s office dictated, would Freddy Krueger really be scary? I don’t think so.

We have the Six O’ Clock News screening every day and the content of that is far scarier than anything Hollywood screenwriters can conjure up.

For me, horror films offered a world of imagination and alternate reality, and the screen violence of the Elm Street films functioned on the same level as The Road Runner or Tom and Jerry; it’s not realism, even as a kid I understood that televisions don’t sprout heads and dispense witty one-liners before doing someone in. These fantastical special-effects sequences are as animated as any Looney Tunes cartoon. In the sixth entry, Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare, the titular villain rolls out a comically oversized bed of nails straight out of the ACME Corporation catalogue as he anticipates a terrorised teen to land on it. If that’s not Wile E. Coyote material, I don’t know what is.

Freddy Krueger

A nervous energy always buoyed the car trip home from the video shop, having picked out a VHS that displayed some horrific-looking creature like Pinhead from Hellraiser or the Ghoulie from, well, Ghoulies; not knowing what was in store for you within those tape reels fuelled an illicit excitement.

While many videotapes came and went through my machine, few bounced back into them like the Elm Street films, because I found my movie monster hero in Freddy Krueger.

He was scary and he was funny. As the films progressed, so did the humour, and while some would say to its detriment, I disagree; Freddy became a pop-cultural phenomenon and the films reflected the audience appetite for this villain of increasing personality. In fact, it was around the time of the character’s pop-cultural approbation that I discovered him, so that was the version of Freddy that drew me in.

True horror of Elm Street

However, as I got older I realised the true horror of Elm Street comes not from the mayhem that Freddy inflicts, but from the relevant inherent themes.

With maturity came the revelation that the entertaining generic contexts within which the series works is a front for astute social commentary on everyday conflict.

Creator of the franchise, Wes Craven, was a filmmaker of immense social conscience and thematic depth, and he delivered difficult intellectual ideas wrapped up in a neat horror movie package. Looking past that surface reveals an Elm Street which harbours the horrors not of Hollywood bogeymen but those that can reside in any home on any suburban street.

The films offer critical discourse on and depictions of alcoholic, abusive, ignorant, divorced, and damaged parents, and their variously unstable, disturbed, and highly-medicated children. If Freddy is something horrific he is the psychological manifestation of the emotional fallout of the domestic conflicts within these homes.

Important subtexts

Those are important subtexts that simmer behind the Elm Street façade and are the reason I wrote this book.

I wanted to ruminate upon the reasons it resonates with millions of moviegoers.

I don’t believe it’s due to merely providing thrills and spills with immense skill; that’s a major part of it, but I feel the themes afford audiences much empathy with troubled young characters and their anxieties which come from within their own families. Those issues are not exclusive to the realm of horror, they can occur within our own home and we can all potentially experience our own dalliance with a Freddy Krueger.

Words from Freddy

Freddy himself, Robert Englund, summed it up sagaciously when he said to me, “When the young kid rents a Freddy movie on a Friday night and they turn off the lights and enjoy it with some pizza, they are just excited by this wonderful horror movie experience; they aren’t thinking about all those intellectual themes…but over time, as the kid grows up, they will understand them and they will mean something.”

That is exactly how Elm Street worked on me, and I’m glad it did, because the result of that lasting impression is the release of my fourth book, Welcome to Elm Street: Inside the Film and Television Nightmares.

Wayne Byrne is an author, journalist, and film historian. He has written for publications including Hot Press Magazine, The Irish Times, Film Ireland, and is a regular guest lecturer at Dublin Business School.