Portlaoise|Joe Curtis|Wordwell|ISBN: 978-1-9161375-7-8|€16.99

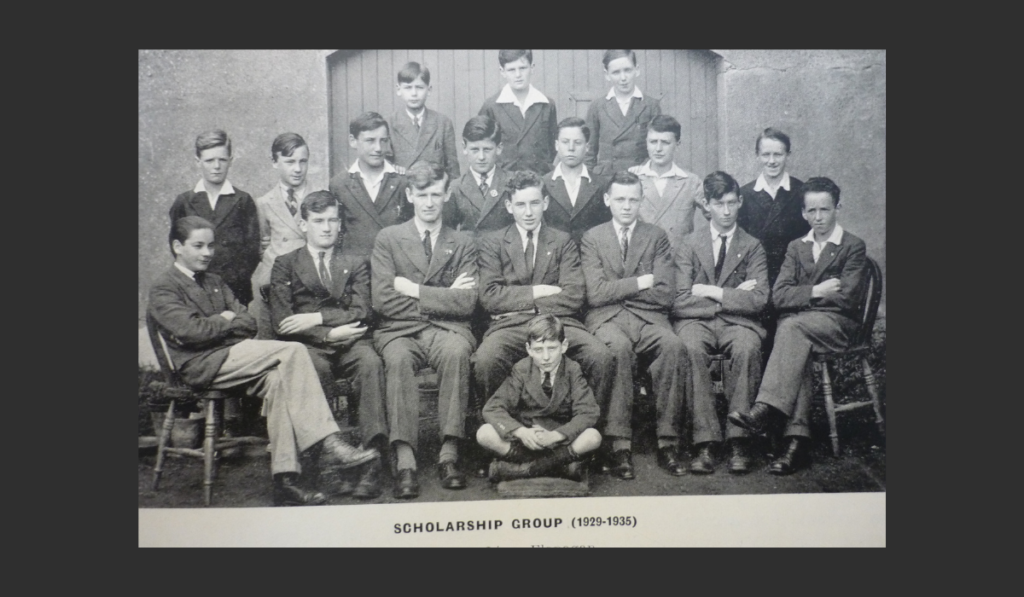

In his book Portlaoise, author and local historian Joe Curtis explores the visual history of Portlaoise as it developed up to modern times, touching on different aspects of the town from education, to religion, to how people made a living—all brought to life with incredible photographs.

Read an extract from the introduction here, interspersed with some of the compelling images included in the book.

The Fort

The English stronghold in Ireland in the sixteenth century centred on the Dublin region, called ‘The Pale’, but they were continually trying to penetrate further into the territories of Irish chieftains.

In the midlands, around the year 1548, the English built a fort in the Laoghaise (or Leix) region to guard against attacks by the O’Moores and O’Connors, and this was known as Fort Protector (after Lord Somerset, the Lord Protector of the Crown).

In 1556, Queen Mary I decided on the ‘plantation’ of the Irish territories by confiscating their land and giving it to English ‘settlers’, calling the area Queen’s County and stipulating that Fort Leix (Port Laoghaise) be renamed Mary Burgh. In 1570, her successor, Queen Elizabeth I, granted a charter officially making the town into a borough, a status it held until 1830.

The fort was roughly square in shape, encompassing about 2 acres, and various houses and other buildings sprang up around the outside, including St Peter’s church on the west side, which is reputed to have been built in 1560. Fighting between the new English settlers and the native Irish resulted in the town being badly damaged a few times, and it was reported that in 1598, the fort housed up to 200 soldiers and a few horsemen. After the Cromwellian campaign in 1650, the fort was abandoned and partly demolished by the Parliamentarians under Hewson.

The Rory O’Connor School of Dancing in Portlaoise in the 1970s (Courtesy of Redmonds Photography, Roscrea)

However, in the eighteenth century, the town outside of the actual fort walls continued to develop, and a long main street and market square set the general pattern for its layout. Some of the buildings were probably single storey and built of mud, to be rebuilt later in stone to a greater height.

Redevelopment of the town continued into the next century; the new St Peter’s church (Anglican) was built further to the west in 1803/04, and various public buildings and institutions followed over the next few decades.

However, the town layout was dictated by the fort walls, with Main Street on the south side, Railway Street on the west, Tower Hill on the north, and Church Avenue to the east. Today, there are numerous remnants of the old fort walls to be seen in these streets, while other stone masonry is incorporated into new buildings or new boundary walls. The curved north-east ‘bastion’ of the original fort is still standing, and is not as powerful as it looks, since the inside is hollow, and the stonework is not thick.

There was a sixteenth-century ‘Stone House’ on the east side of the fort, which later became the county infirmary, and its circular tower was incorporated into the Presentation Convent when the nuns purchased and redeveloped the property in 1824. Presumably this is not a spelling mistake, instead of ‘Store House’, meaning a shop of some sort, as a store could be expected to have been located inside the fort for protection. Assuming that the word ‘Stone’ is correct, would this imply that other buildings in the town were inferior, built of mud or timber?

The town was renamed Portlaoise in the 1920s, meaning ‘Fort of Laoghaise’, but people who were born in that era continued to use the name Maryborough (pronounced ‘Mar Bra’ by locals) throughout their lives, doing so right up to the present day.

Portlaoise|Joe Curtis|Wordwell|ISBN: 978-1-9161375-7-8|€16.99